No sign for sadness

I never imagined my PhD would lead me here. When I began in 2022, my goal was to explore digital mental health in Bangladesh. That research opened up a space I had never seen before: the mental health of Deaf communities. It is, without question, one of the most overlooked public health issues in global mental health.

I’m a medical doctor from Bangladesh, now finishing my PhD in digital mental health at the Faculty of Information Technology, Monash University. I also serve as Policy and Advocacy Lead at the Mental Health Council of Tasmania. My journey spans global contexts including Africa, Southeast Asia, the UK and now Australia. But this work with Deaf communities has changed me in ways no other project has.

When there’s no word for depression

The first workshop I ran with deaf participants in Bangladesh was sobering. We presented a series of emojis and asked participants to describe them. The participants recognised happiness. But when I used the word “emotion,” they asked, “What does that mean?”

Even more striking, many had never heard of the word “depression.” They knew sadness, but had no sign for anything beyond it.

I stopped the workshop immediately.

Globally, there are over 466 million people with hearing loss. Yet deaf mental health barely features in the literature. In Bangladesh, I found not a single published paper on the topic. Even internationally, there are perhaps 20 or 25 peer-reviewed articles at best. This is not just a gap. It is a void.

Building a language for feeling

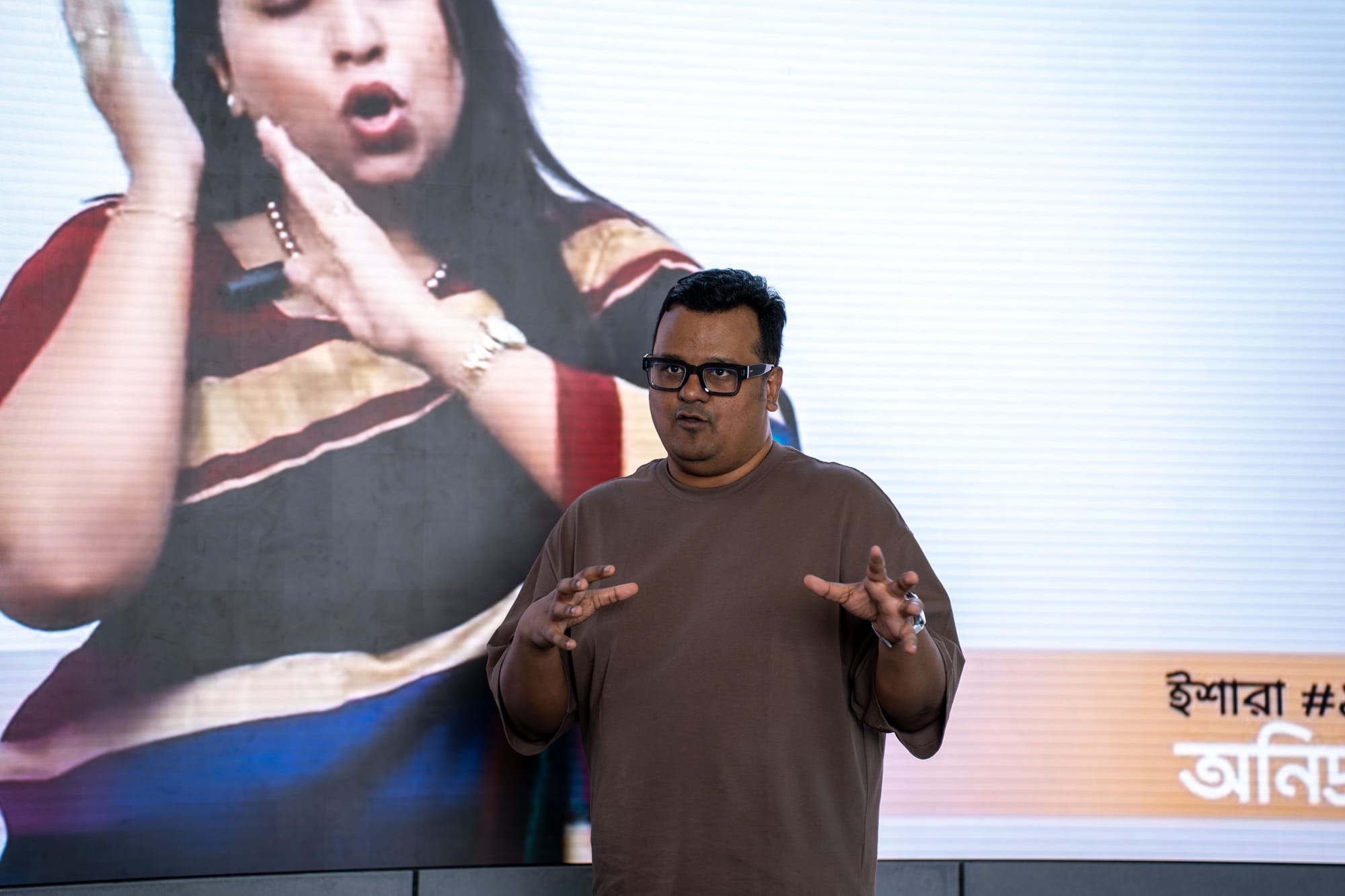

The first step was foundational: build a Sign Language Bank for mental health.

This was not a top-down process. It was fully co-designed. Deaf people, caregivers, sign language interpreters and mental health professionals worked together. We started with 130 terms and distilled them down to 64 essential concepts, each one given a culturally appropriate sign.

Many terms did not exist in Bangladesh Sign Language. We had to borrow from American and British Sign Languages and modify them with community input to suit local context.

Instead, they said:

- Teach us how to manage anger

- Help us understand restlessness

- Show us how to deal with loneliness

- Let us hear from others like us

- Give us stories from our own deaf community

We delivered:

- A 17-minute Sign Language Bank video on YouTube

- Short 10-second reels for each of the 64 terms

- Video explainers on mental health, physical versus mental health, and loneliness

- Personal stories from deaf participants

- A series of electronic flyers in English, Bangla and Deaf Bangla (a simplified version used by many Deaf individuals)

- Community-led feedback through a WhatsApp group of 200 Deaf participants

Making visibility visible

Inclusion is not a tick-box. It is not about adding a tiny interpreter window in the corner of a video. As the community told us, the interpreter should be full screen. The person signing should be from their community or someone endorsed by them. The language should be theirs, not ours.

We also avoided terms like “impairment.” Deaf people told us clearly, “Just call us Deaf. That’s who we are.”

These may sound like small details. But they are fundamental to dignity and belonging.

Outcomes, recognition and the unexpected

We launched the full resource bank in March. It is live, public and already in use.

Since then, the project has received global recognition. The Mental Health Commission of Canada listed it among eight global ideas changing lives. I have presented this work to the Prime Minister of Sri Lanka in Colombo, the WHO Regional Director in Singapore, and at major international and national forums, including the eMental Health International Congress in Canada, the Australian Public Health Conference in Wollongong, and SXSW in Sydney. The project has received multiple awards and recognitions from the British Council, the University of Melbourne, and Monash University.

But none of that compares to what happened next.

What I learned

- Deaf mental health is radically under-addressed, even by experienced professionals

- Co-design creates more powerful, relevant and respectful resources

- Mental health literacy starts with the ability to name emotions

- Simpler technologies like YouTube, WhatsApp and digital flyers can be world-changing

- Innovations from low-resource contexts can and do lead global thinking

CALL TO ACTION

Dr M Tasdik Hasan is a medical doctor, PhD researcher at Monash University and global mental health advocate. He is Policy and Advocacy Lead at the Mental Health Council of Tasmania and works across Bangladesh, Africa, Southeast Asia and Australia.