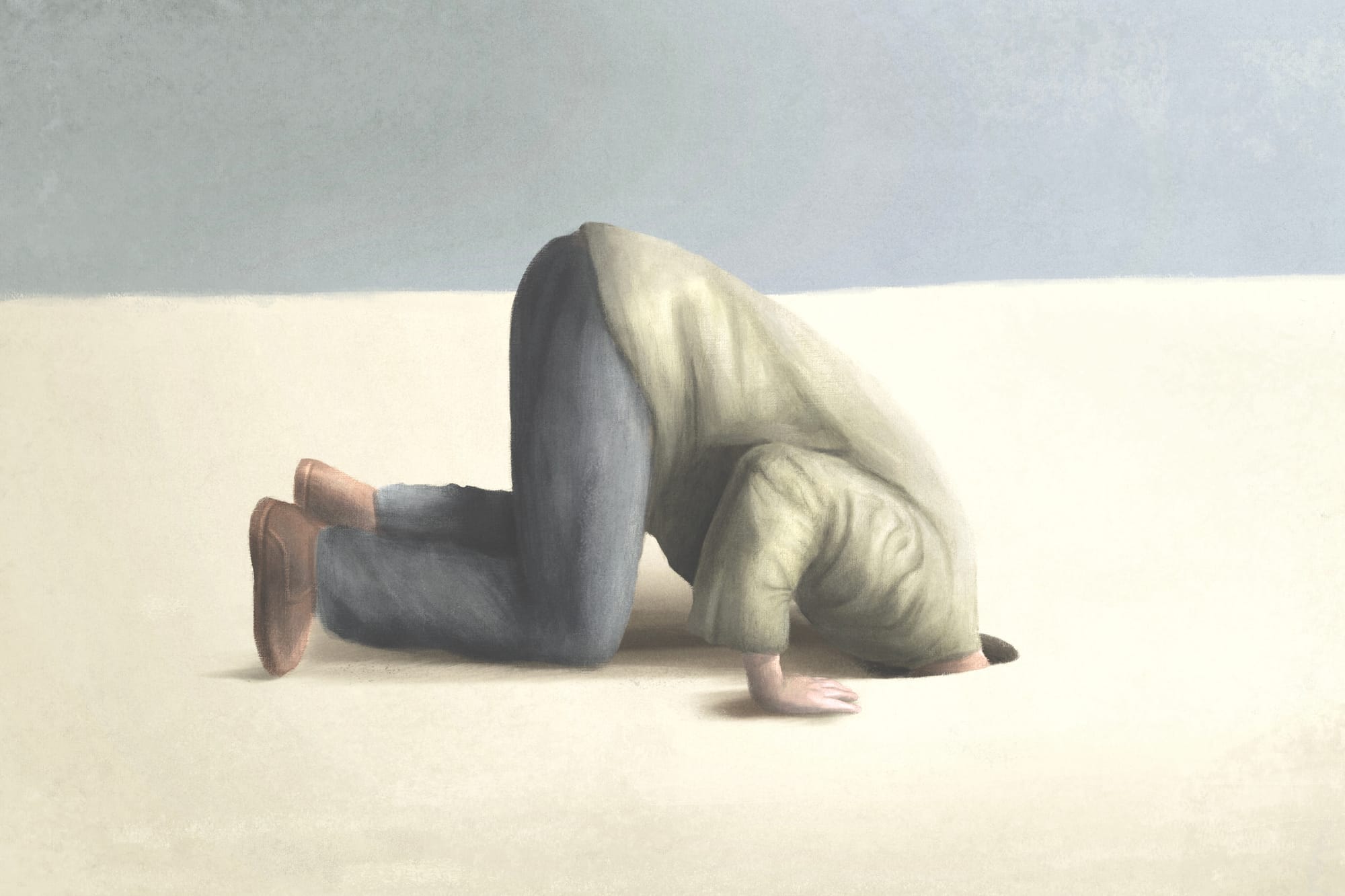

Deadly silence

A Silent Epidemic: Why Eating Disorders Must Be Named in New Zealand’s Suicide Prevention Strategy

New Zealand's new Suicide Prevention Action Plan 2025–2029 aims to lessen suicide's impact across our communities. It aims to highlight fairness, prevention, early help, and support. As someone working with families affected by eating disorders, I see much to welcome - but something vital is still missing. Again.

Eating disorders aren't mentioned. Not once.

This isn't just about missing words; it's a dangerous silence. Those of us with personal or professional experience of eating disorders have been flagging this for years.

I am witness

I'm not a clinician or policymaker. I'm a mother, a carer, an advocate. I've watched my own family battle these illnesses - despite early awareness, astute parenting, and my best efforts with limited support. I've also stood alongside other families carrying the same burden in a system not designed to meet them.

Serious, complex mental health conditions

Eating disorders aren't uncommon or rare. They're not simply about food, or limited to teenage girls, or vanity. They are serious, complex mental health conditions which affect our whole community, often overlooked or misunderstood until the harm is significant. When we leave them out of suicide prevention plans, we're not just overlooking a risk; we're choosing not to face it, and people are paying the price.

Left out, but why?

What's hard for me to grasp is that many senior health professionals I’ve connected with, quietly acknowledge their own experiences with eating disorders - personally or in their families. It's more common than people realise. So if we know this, if it's part of our shared reality, why are we still creating national strategies that leave eating disorders out?

We often hear the strategy can't "name everything." But this isn't about listing every possible factor. It's about recognising known, measurable risk affecting thousands of New Zealanders yet eating disorders continue to remain unseen.

I like to think there is hope.

The Mental Health Minister has called eating disorders a "health crisis" and announced a refresh of the national strategy for them. That's a step forward. But unless that work genuinely connects to suicide prevention efforts, we risk a fragmented system -where people fall through the cracks because no one is looking at the complete picture.

● Naming them: Eating disorders should be clearly acknowledged in suicide prevention frameworks and public health campaigns. Recognition leads to resources.

● Screening for them: Mental health, youth, and primary care services should regularly check for eating disorder symptoms, especially when suicide risk is present.

● Funding effective treatment: We need accessible, timely, and well-funded eating disorder services—from early help to long-term recovery support.

This isn't about fighting for attention. It's about speaking the truth. The connection between eating disorders and suicide is clear. The cost of ignoring it is too high. And the people most affected deserve better than another round of national planning that leaves them unnamed.

Eating disorders need to be part of this conversation. Not later. Now.